I’m often asked what camera I use and what film I shoot.

This isn’t really a story about either. It’s a story about craft. About what sits underneath those questions, and why the choice of tools matters as long as they serve the the process and work.

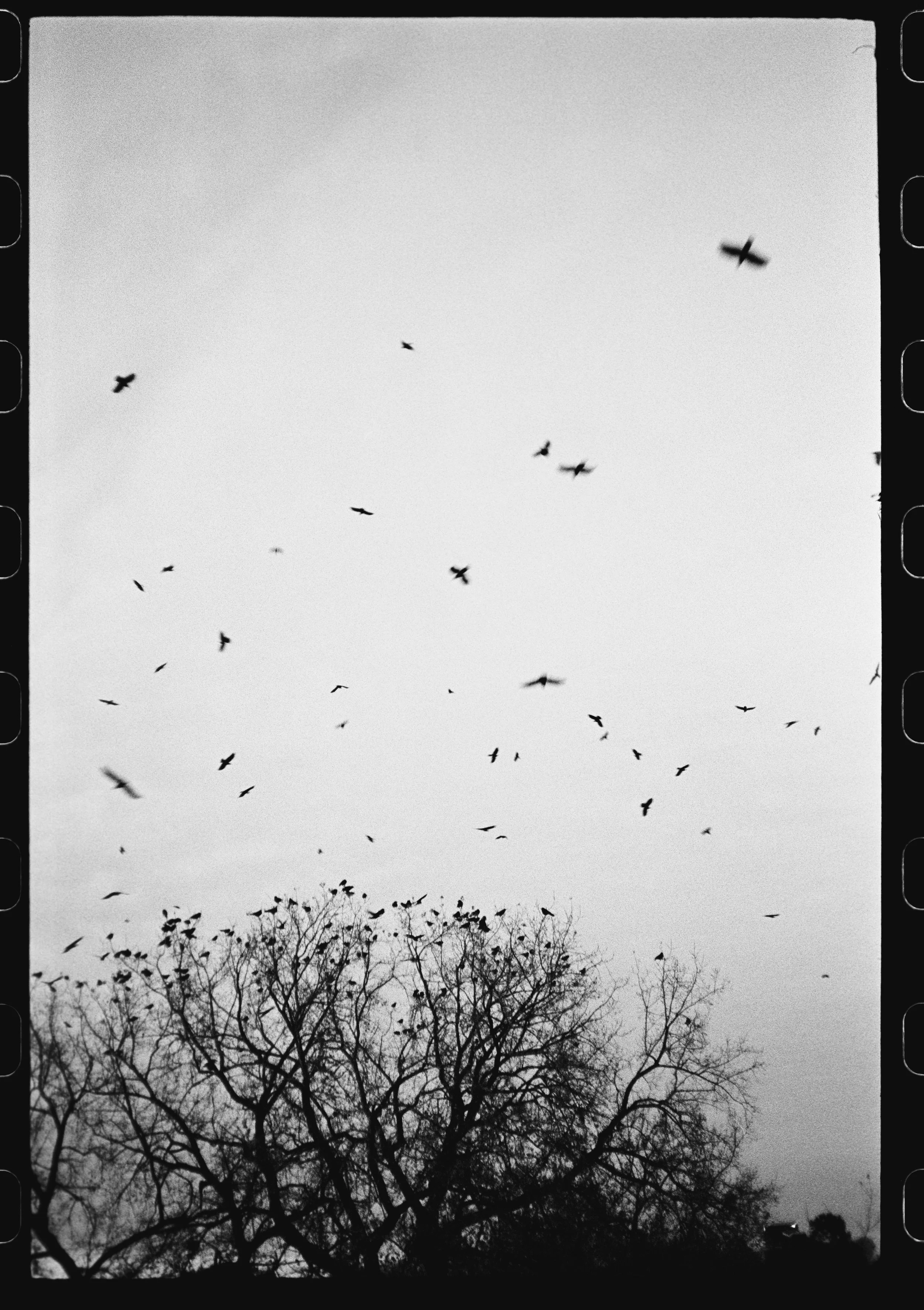

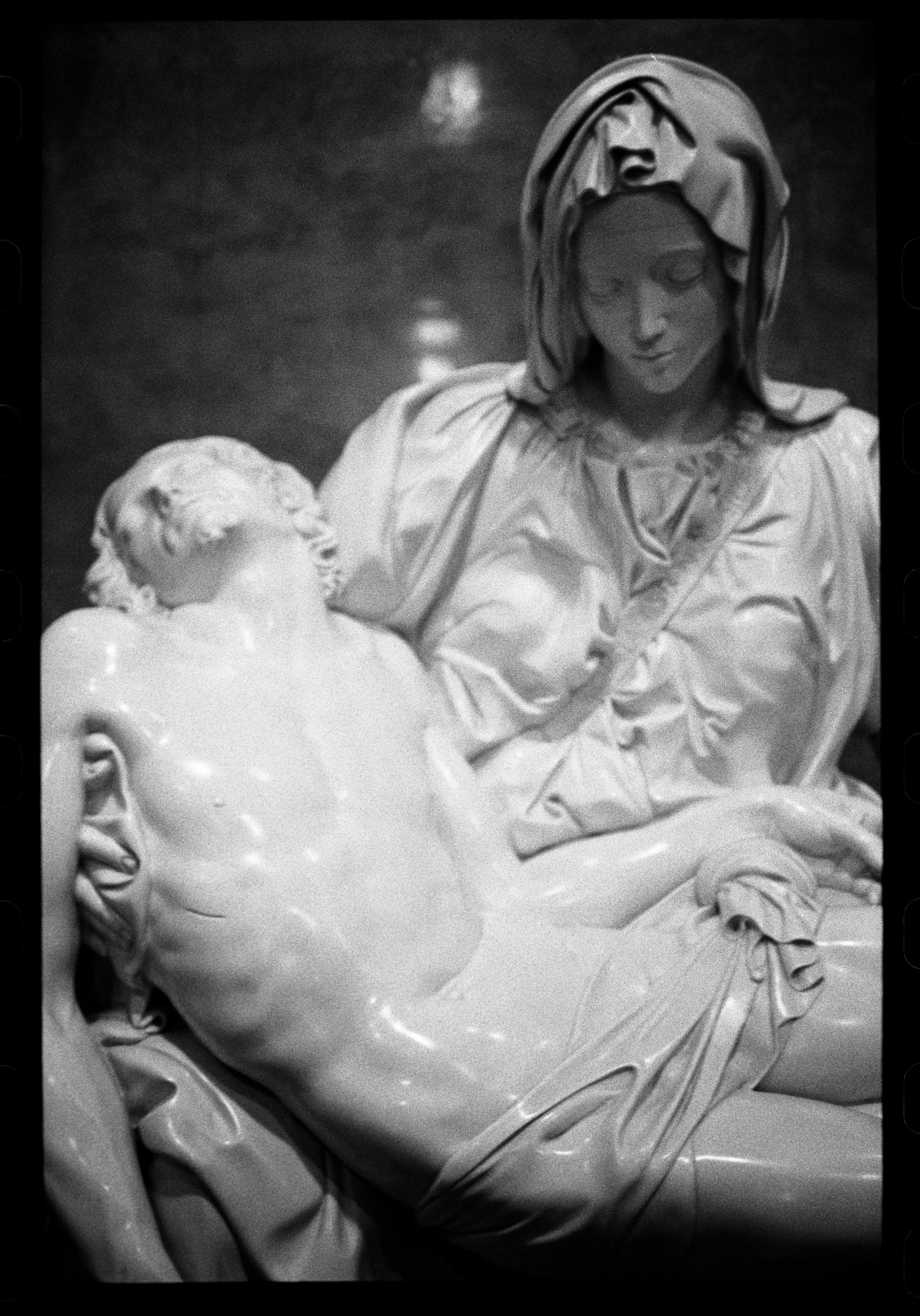

At some point, I realized I think about photography less like “painting with light” (as Miroslav Tichý once described it) and more like sculpture. The way Michelangelo talked about the figure already existing in the stone, and the work being the removal of everything that doesn’t belong to it, always felt closer to the truth.

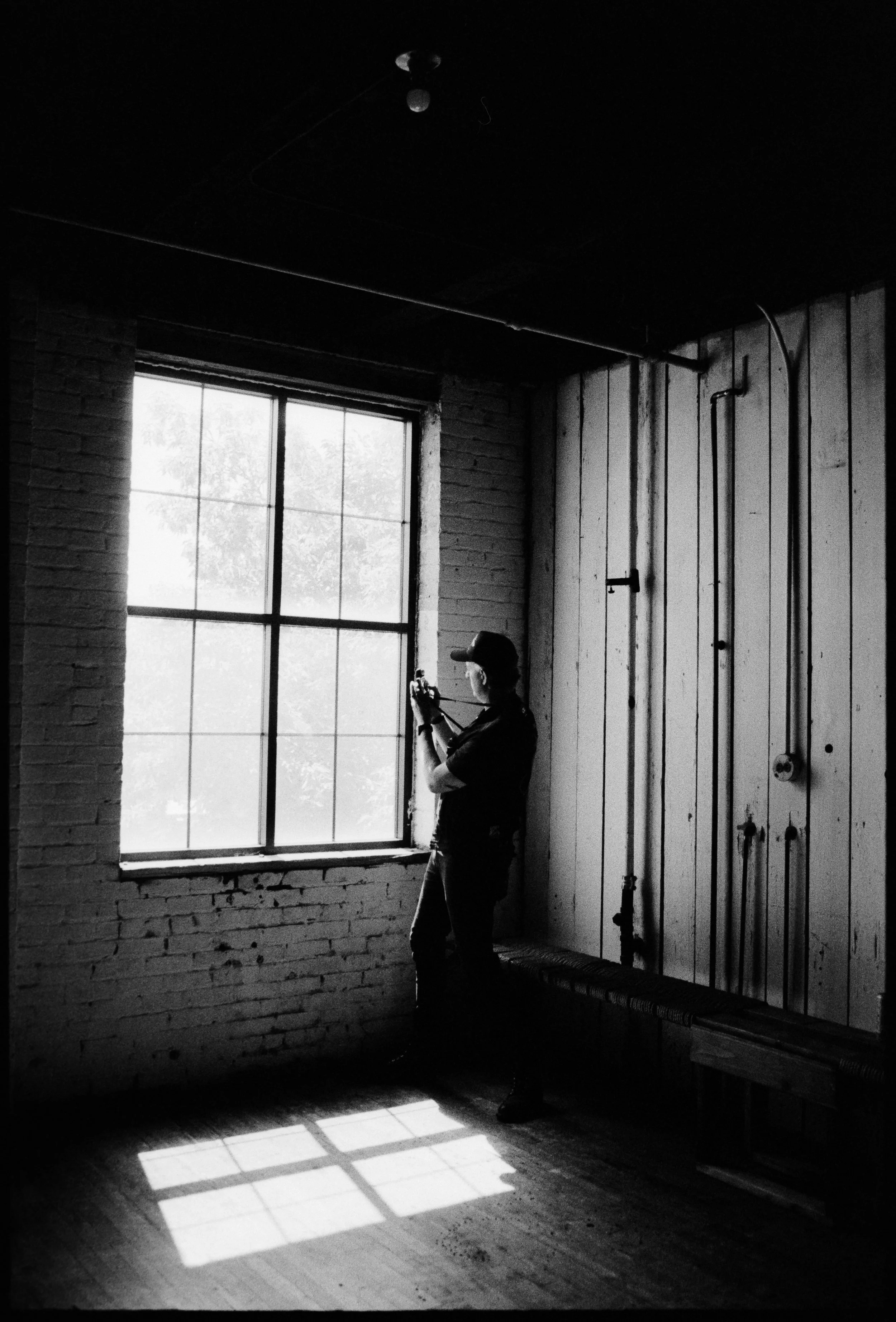

Photography, to me, is inherently subtractive. With the entire world in front of you, the work is deciding what to leave out of frame.

David, Pietà, the figures for the Medici Chapel, and even the unfinished Apollo. Each completely different, but all carved from the same Carrara marble, selected before any work began.

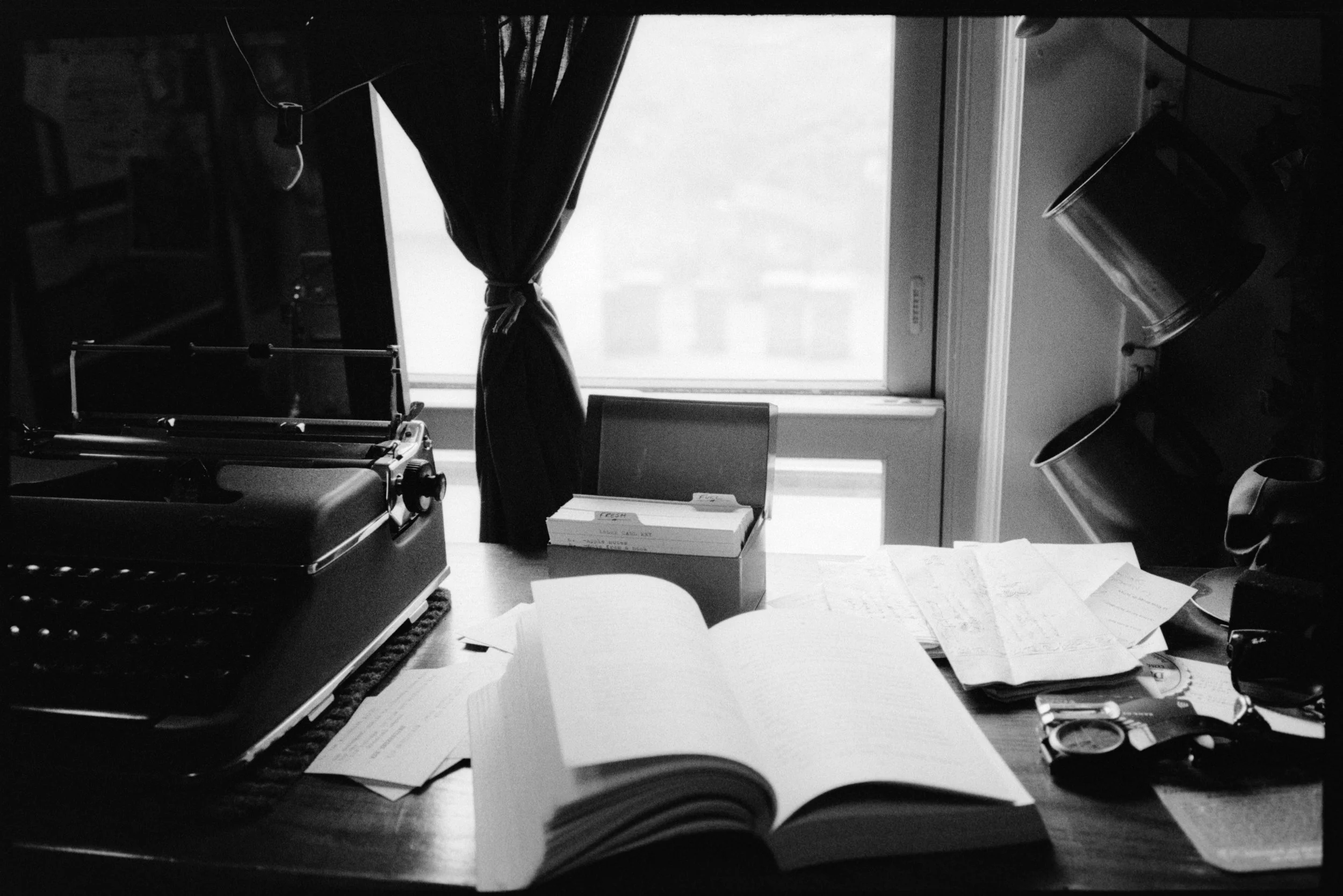

When I first dove into photography, I didn’t have language for any of this yet. I just knew that certain photographs stayed with me longer than others. Over time, a pattern emerged. Most of the images that truly moved me were made on black and white film, using tools made before I was born, by people who are no longer alive.

Since I couldn’t send them a DM, I bought their books instead. I started collecting what I call Virtual Mentors: Willy Ronis, David Hurn, Jim Marshall, Jill Freedman, Elliott Erwitt, Jill Furmanovsky, Fan Ho, Yuka Fuji, Yul Brynner, Bill Brandt, and Allen Ginsberg, just to name a few.

Studying the clues they left behind, I started noticing something beyond subject matter. Certain photographs carried a feeling that stayed with me, separate from whatever was happening in the frame. I began chasing that feeling in my own work.

I realized it wasn’t a singular image I was looking for, at least not in the traditional sense. It was more of a way a photograph could feel once it exists.

Not a subject, but a state.

A tone.

A vibe.

A through line.

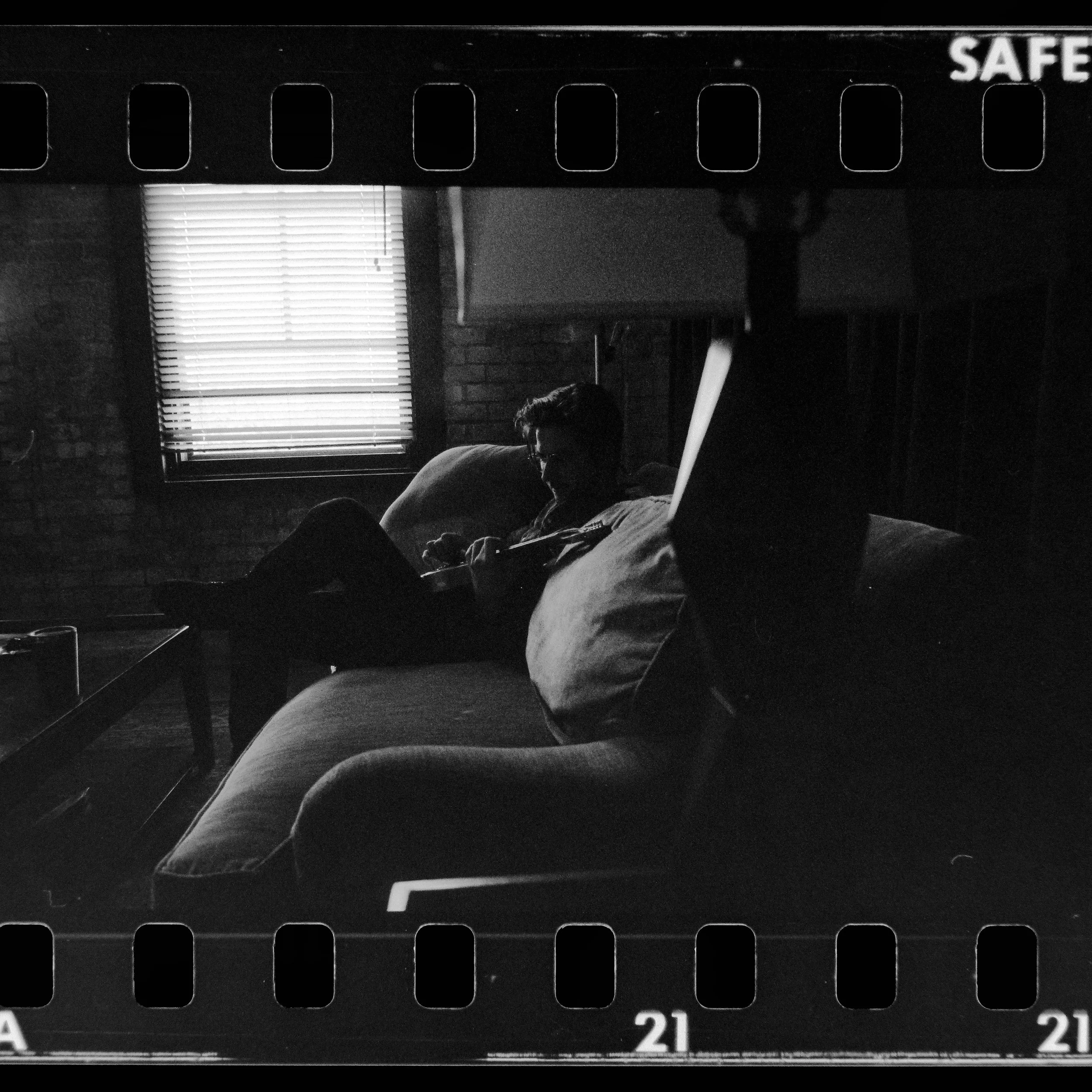

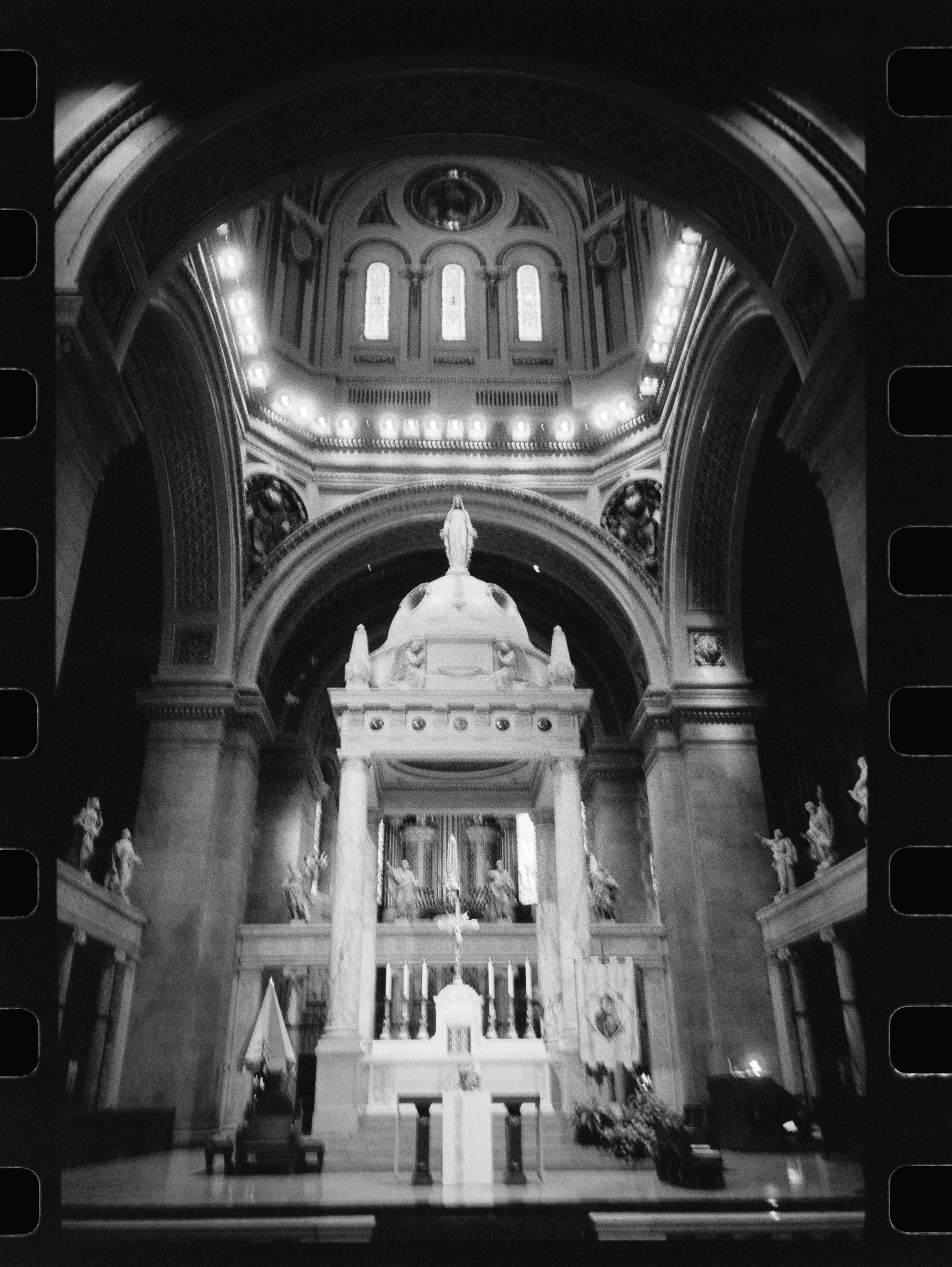

That’s why I kept coming back to film. It was the only way I found I could get there. It’s slower. It’s frustrating. It’s expensive. But it gives me something I can’t get digitally, both in the process and the end result. Film resists certainty. It slows you down and forces a conversation between intention, moment, and material.

A film photograph feels less post-processed and constructed and more honest somehow as if everything I’m looking for is already there, and my job is simply to pay attention.

Somewhere along the way, I heard about Plato using the words εἶδος (form, appearance) and ἰδέα (idea) interchangeably. Not “ideas” the way we mean them now, but essence. The thing underneath the thing.

The subject can change. The essence stays the same.

Different song, same voice.

In ‘Camera Lucida,’ Roland Barthes talks about studium and punctum. What we recognize in a photograph, and what unexpectedly hits us. The unmade images that keep me obsessed tend to live somewhere between the two.

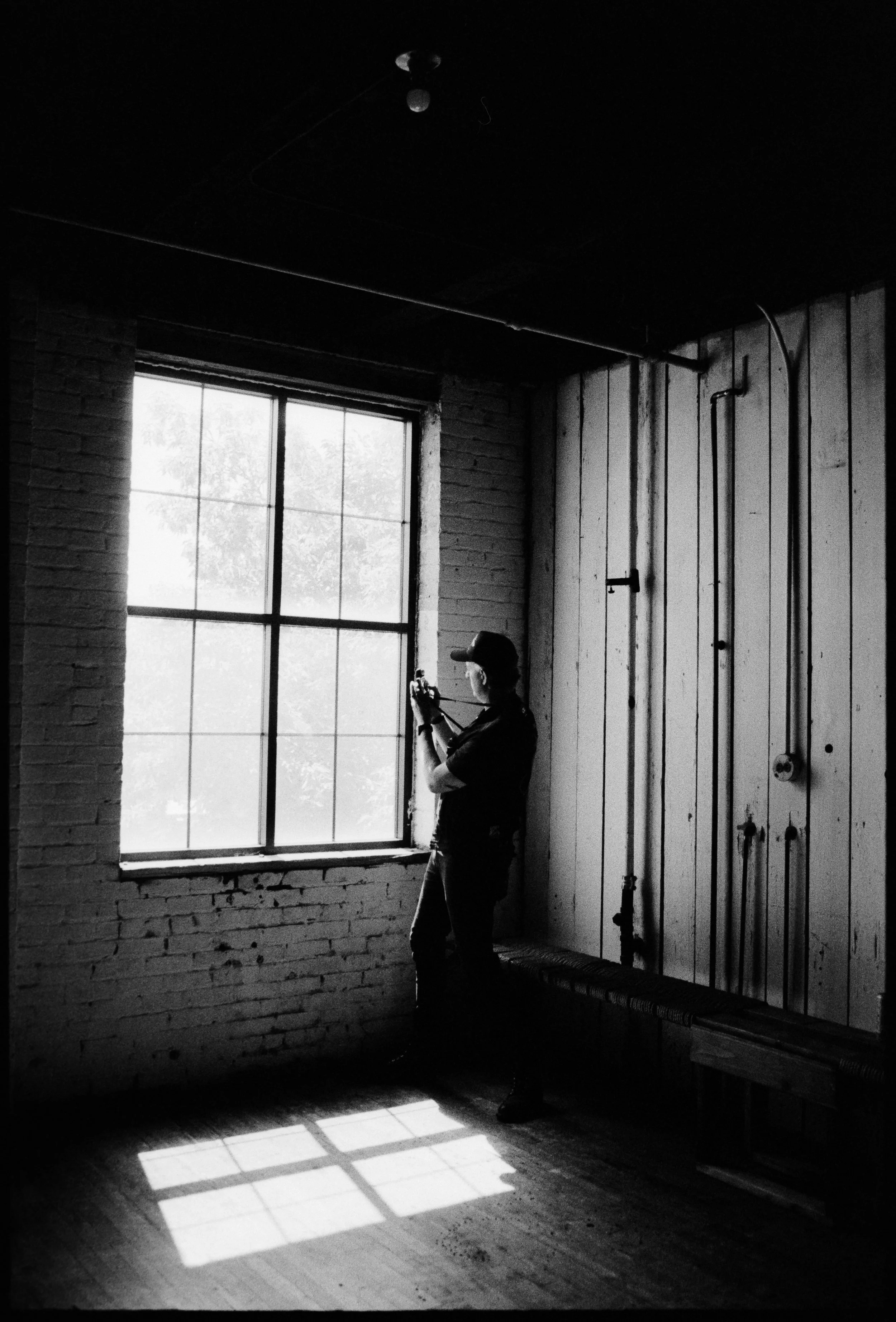

To be clear, I’m not chasing perfection. I’m chasing alignment. Something closer to A440. A way of tuning my eye so I can recognize those rare moments when idea and image agree. Moments where the tools and materials finally disappear and, as Dorothea Lange put it, become an instrument that teaches you how to see without a camera.

When that happens, a photograph feels less like something I made and more like something I finally found.

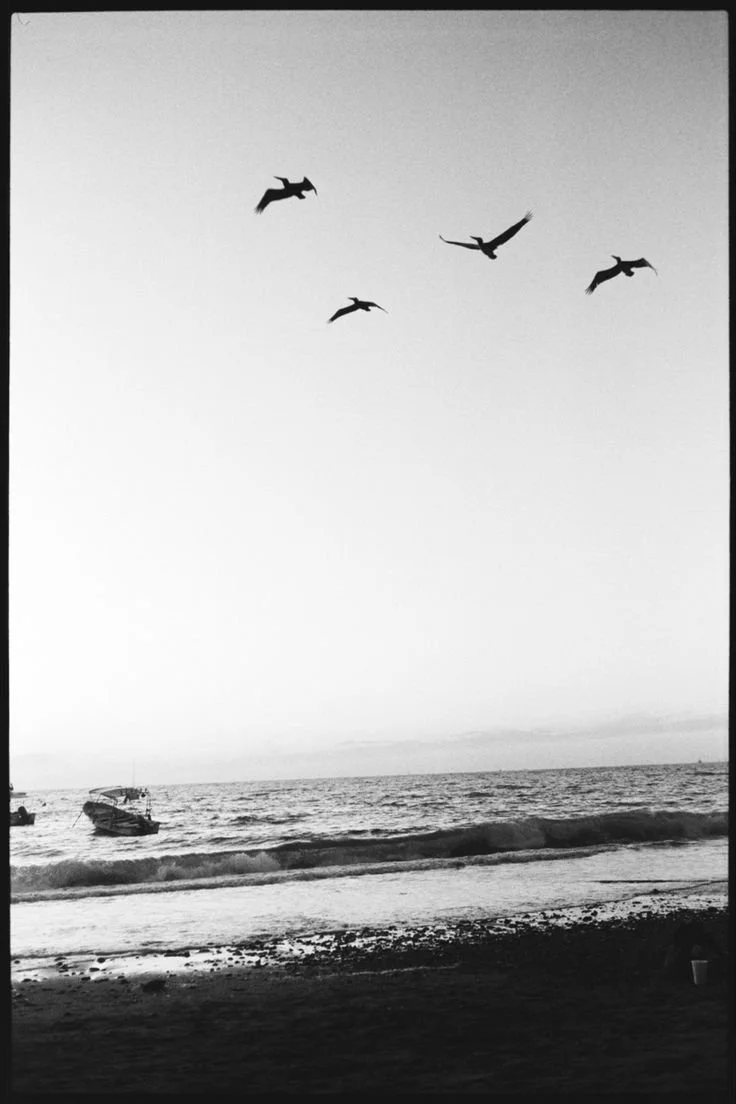

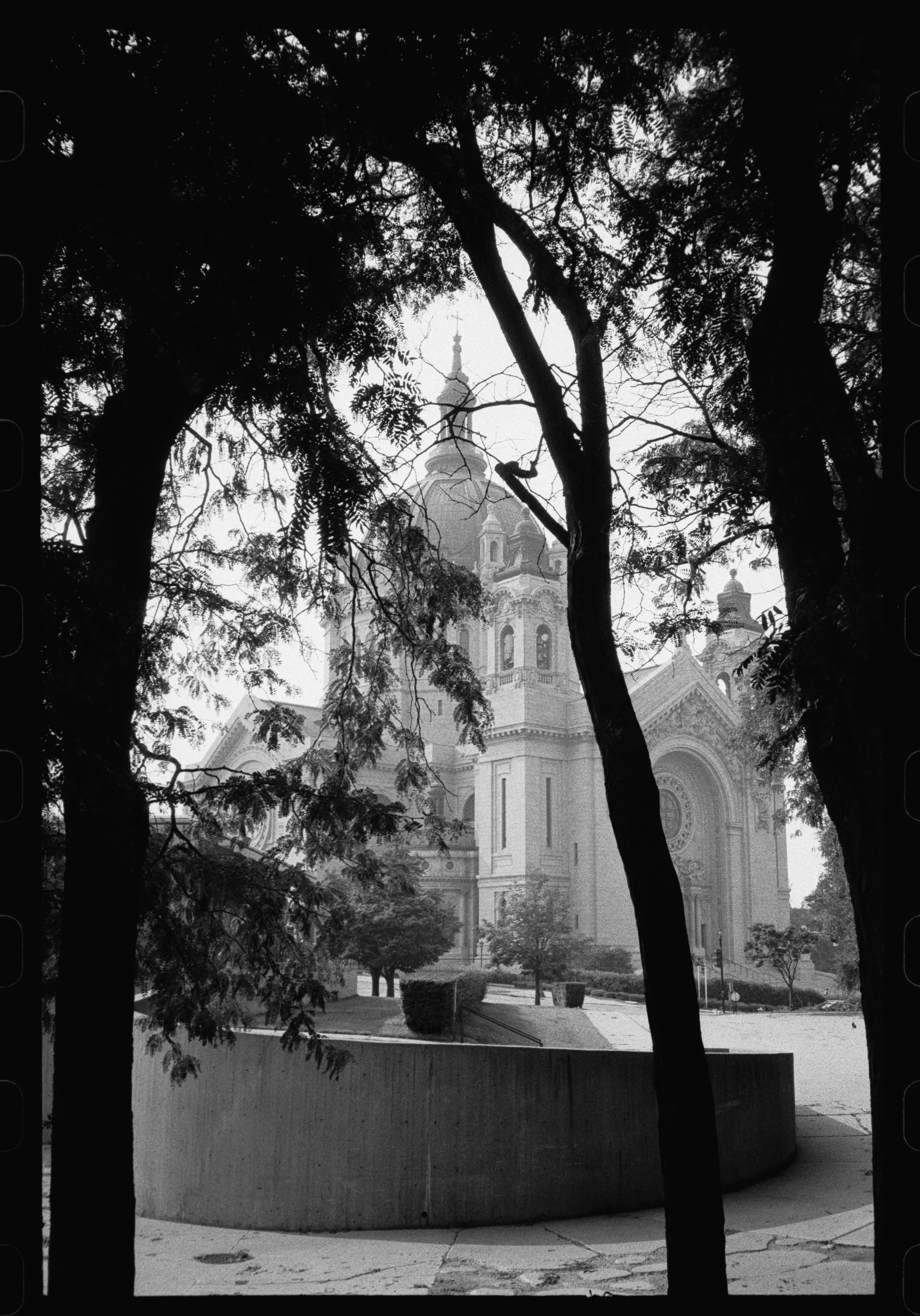

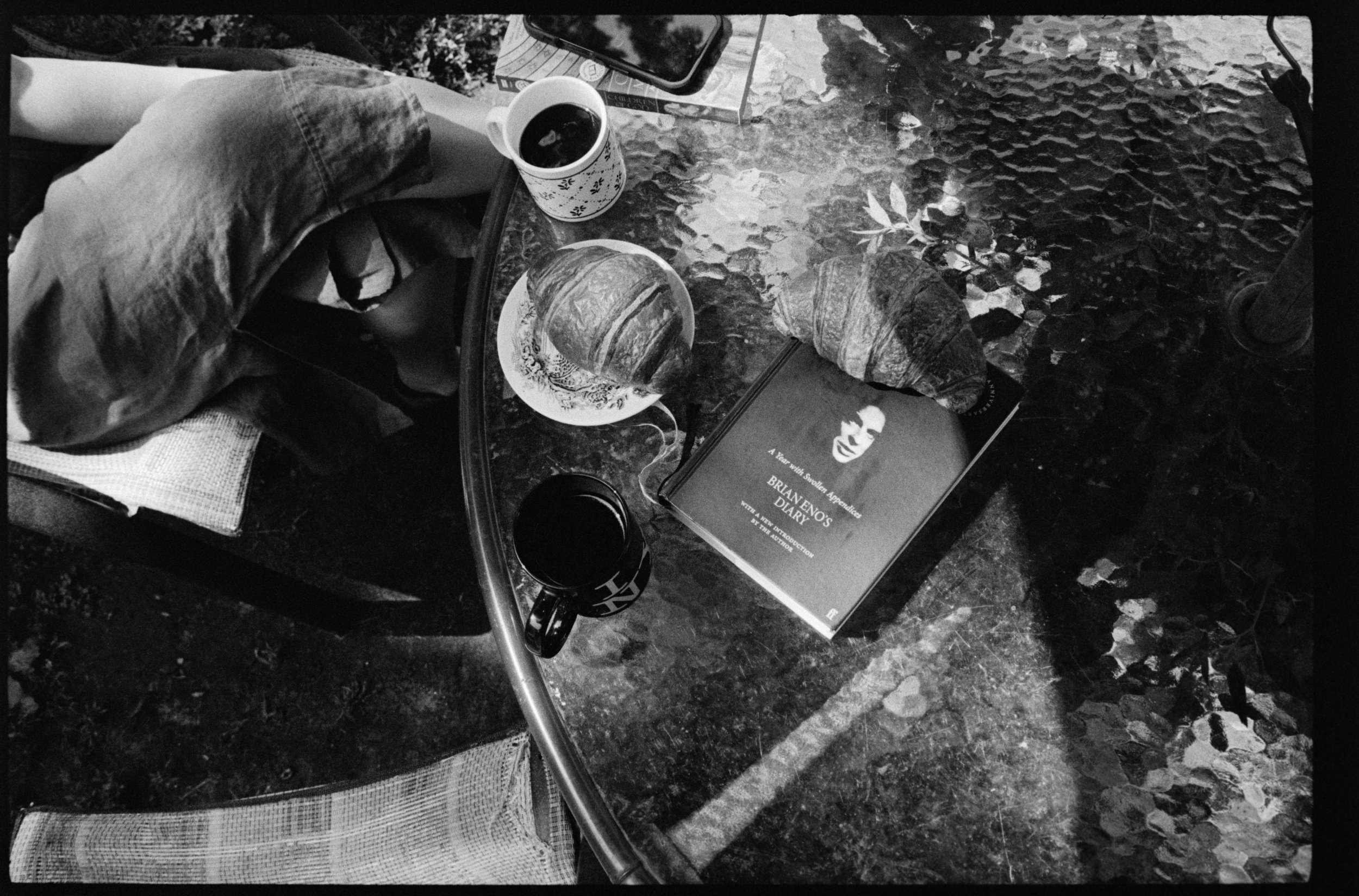

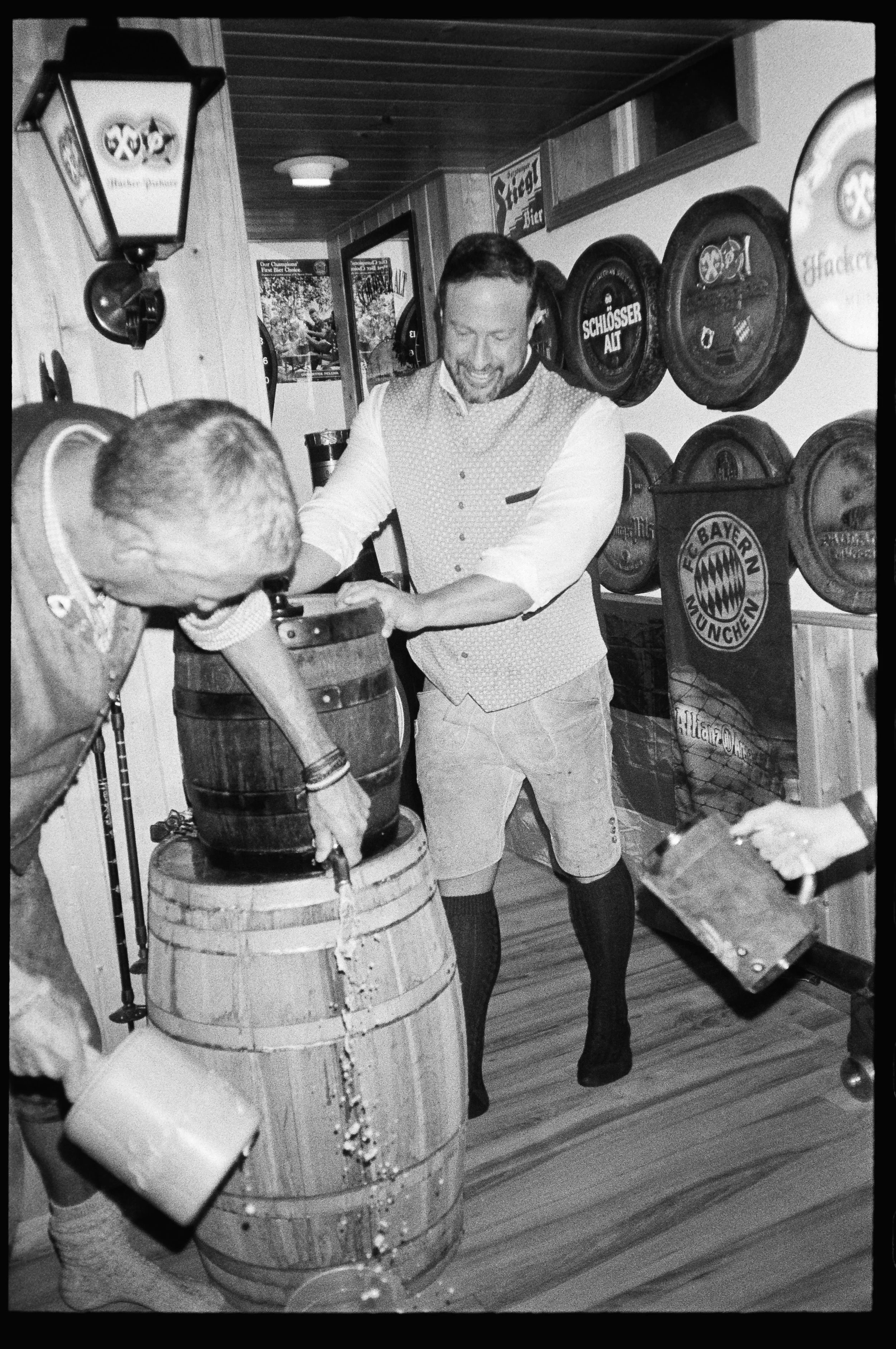

These photographs are the closest I’ve gotten so far.

Oh wait… that’s right… I did want to talk about the tools and process. I musta had a philosophical blackout. Although my camera and lenses used to change more than Tom Cruise trying to do an Irish accent, my film and developing process (after years of experimenting) remains the same:

On Cameras & Lenses: My favorite cameras seem to be made from brass. My favorite lenses seem to be 40mm.

On Film: My local mom-and-pop photo developer in Minneapolis, Fast Foto, generously supplies me with used 35mm film cassettes. I load them with HP5 that I purchase in bulk (using a dark bag and a vintage Watson Model No. 100). Although almost all my favorite photographers listed above shot with Kodak Tri-X 400, I shoot HP5 because of the following: it dries fast, it dries flat, it has mind-blowing latitude, it scans and prints beautifully, and it’s inexpensive. (Note: My wife Sarah and I travel abroad regularly, and she’s asked me to shoot color film when we do. Kodak UltraMax 400 is my color love language.)

On Shooting: I primarily shoot HP5 at box speed (ISO 400) and meter by eye. (Fred Parker’s “Ultimate Exposure Computer” is worth a read for any photographer.) Because I’m lazy, I don’t change any of my process when my camera’s loaded with Kodak UltraMax and have never had an issue.

On Developing: I develop in Kodak HC-110 and keep it simple: Dilution B, 8 minutes with room-temp tap water, skip the stop bath, Ilford Rapid Fixer for 5 minutes, rinse, lazy splash of Kodak Photo-Flo, finger squeegee, wipe with a KimWipe, and hang to dry. When HP5 “snaps” from curved to straight you know it’s done.

On Scanning/Editing: I use Negative Supply’s light and film holder and DSLR scan with my Leica SL2-S and a macro lens. Then, in Lightroom, I edit the DNG files using Negative Lab Pro before cutting into negative holders for contact sheets.